“But we need progress measures!” said the primary headteacher at a recent meeting, and this is a common response to the question of whether we could live without them. Understandably, schools that are prone to low attainment want progress measures to help mitigate the issues that low attainment inevitably brings. If key stage 2 results are below national figures it’s nice to have progress scores that are in line with average or even above (Green!). We are taking account of pupil’s prior attainment – as we should – and those progress measures are front and centre of the performance tables for all the world to see. It seems right and proper this way.

But just how accurate are progress measures? And what is the likelihood that schools may ‘tweak’ assessment data to boost them?

At this point it’s worth bearing in mind that, for all it’s complexities and dark arts, Progress 8 at least involves standardised assessment data at each end (KS2 and GCSE); and that secondary schools are not in charge of their own baselines. They do not administer the key stage 2 tests that form the baseline for their main accountability measures.

Now let’s consider the situation in primary schools. Progress is not measured from the start of statutory education (yes, the baseline is coming and that has its own issues); it is measured from key stage 1, nearly half way through the primary phase. KS1 results, whilst they may be ‘informed’ by a test, ultimately are based on a teacher’s judgement, and with the best will in the world, those judgements are subjective. Now let’s factor in the high stakes and consider the potential effect on KS1 outcomes when we know they will form the baseline for future progress measures. Then let’s throw the infant-junior (or first-middle) school issue into the mix. Suddenly we have a situation where the vast majority of schools are in control of their own baseline alongside a smaller group that are not. It’s like allowing 90% of marathon runners to time their own races from a point of their choosing whilst the remainder have to carry timing chips that are activated before they have even begun to lace up their shoes.

And let’s not forget the various bodges made to ensure inclusion of as many pupils as possible in the progress measures, namely the use of nominal scores for pupils below the standard of the test (which are not properly moderated), and the additional bodge of capping extreme negative outliers introduced to mitigate the issues of caused by the original bodge. And on top of that we have a system that does not recognise the difference between pupils with SEND and those with EAL with equally low start points, which often results in out of reach benchmarks for the former group and very high progress scores for the latter. The introduction of data from special schools in 2017 helped a bit but only for those pupils in the very lowest prior attainment groups.

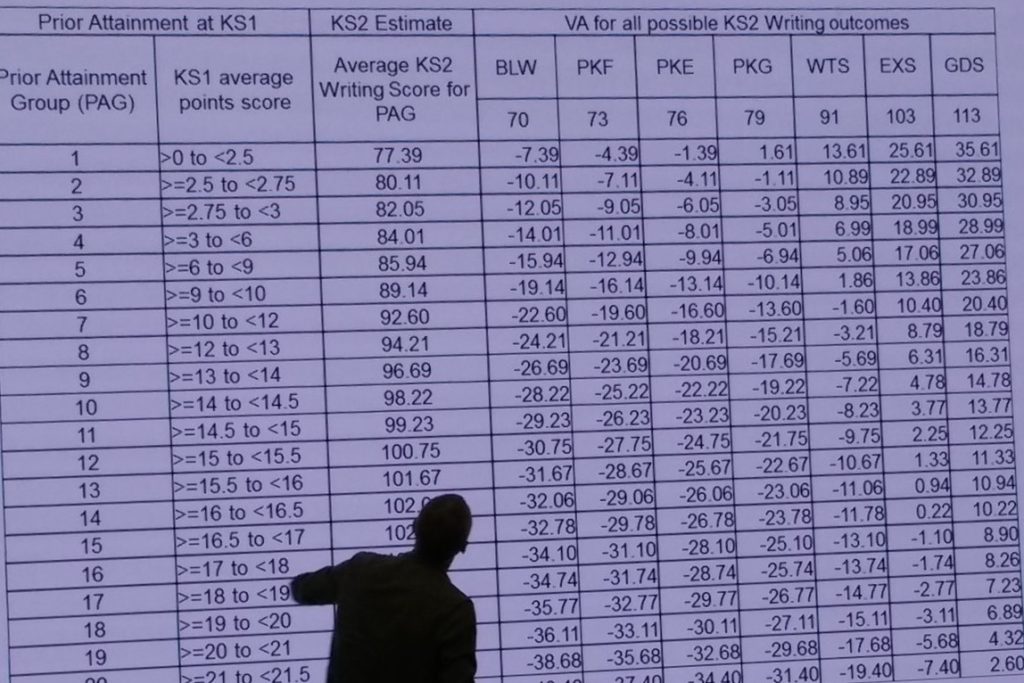

Then there is the writing progress measure, which has to be the most unreliable and poorly conceived measure in the entire accountability system: a broad teacher assessment at each end and yet still involving a fine graded (two decimal point) scaled score estimates at KS2 resulting in 10-12 point swings in a pupil’s VA scores depending on which side of the WTS/EXS/GDS divide they fall. There have been major concerns about the consistency of writing assessment since its inception – which have not gone away – and yet the data is still used to judge school performance. It is some consolation that the DfE and Ofsted issue guidance urging all to treat writing data with caution.

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that all is not right with primary progress measures. From the headteachers that would openly admit that “we don’t do level 3 at KS1 in this school anymore” to the teacher describing the quota system used for KS1 results in her school. Then there are those persistent questions about the effect of various teacher assessment codes at KS2: “If we used this code would the pupil still be included in our measures?”, “Is it better to enter the pupil for the test than to assess them as pre-key stage?” Schools are seeking loopholes and there are still loopholes out there to be exploited. There are even (admittedly rare) cases of schools using the F code – intended solely for pupils that are held back a year – to ensure the pupil’s exclusion not just from progress measures but from attainment as well. Perhaps unsurprisingly, other assessments are not immune to these perverse incentives. The graph of annual phonics outcomes looks a rather dubious, and schools are even being advised to ‘not have too many pupils ‘exceeding’ early learning goals at foundation stage’ for fear it will lower the value of their KS1 results.

In short, it’s a mess. And I can’t see it getting any better in 2020 when we run out of KS1 levels.

I’m all in favour of a basket of measures but only if those measures are not a basket case. So what data can we trust? This may not be very popular, but beyond the KS2 test scores in reading, maths and SPaG, not very much. Yes there are concerns about testing at key stage 2, but in terms of data, it’s about as reliable as it gets: it’s standardised both in terms of assessment and – give or take a few cases – administration. We can report percentages achieving expected and high standards, and average scores with a reasonably high degree of confidence. This data can be shown in the performance tables, ASP and IDSR over the past three years with indicators to show if results are significantly above or below national figures, and whether they have significantly improved or declined. In addition, perhaps there could be a statement that tells us if results are significantly above, below or in line with those of contextually similar schools. This is useful and reliable data that are not affected by the perverse incentives, quirks and bias of the progress measures.

Yes, I understand why schools want progress measures – those with lower attainment would understandably be made nervous by its absence – but should we continue with unreliable measures that can be and are manipulated?

Bad data is, after all, not better than no data at all.